Ear Training: Develop Your Musical Ear

Ear training is a fundamental discipline of musical learning that goes far beyond "having a good ear." It's the systematic process of training the auditory system and the brain to perceive, discriminate, memorize, and integrate musical elements with precision and depth.

In a context where music is transmitted primarily through sound, the development of auditory abilities is inseparable from comprehensive musical training.

Auditory perception is not a passive act of simply hearing sounds. As neuroscientific research has shown, listening to music is one of the most complex cognitive processes in the human brain, simultaneously activating multiple brain regions responsible for emotional processing, memory, language, and motor coordination.

This complexity is precisely what makes ear training so valuable and transformative.

What Is Ear Training?

Ear training, also called aural skills development or auditory training, is the systematic development of the ability to:

- Recognize pitch (frequency)

- Analyze intensity (volume)

- Memorize duration (rhythm)

- Reproduce musical elements through listening

- Discriminate timbre (sound color)

With special emphasis on pitch, which is the most important and complex aspect of musical perception.

Listening as a Progressive Process

Unlike theoretical learning, which is based on symbols and rules, ear training is fundamentally a sensory and active practice. Students must develop a reflective and participatory attitude, using their voice, body movement, and sound imagination as pedagogical tools.

This approach, which places sound before symbol, has deep roots in modern music pedagogy (Pestalozzi, Willems, Kodály, Suzuki) and is supported today by rigorous neuroscientific evidence.

According to Willems, listening can manifest in three progressive forms:

1. Sensory listening (hearing)

Passive perception of sounds without conscious processing. It's the act of capturing sound information from the environment.

2. Affective listening (listening)

Voluntary act of focus and selection. Here the listener chooses which sounds to pay attention to, filtering out irrelevant information and concentrating on what matters.

3. Intellectual listening (understanding)

Deep integration of sound material. The listener analyzes, memorizes, reproduces, and relates musical elements in a meaningful context.

For ear training to be effective, the process must always progress according to this sequence:

Listen → Imitate → Recreate → Recognize → Transcribe → Internalize

Each phase builds on the previous one, allowing learning to be deep and lasting.

Start Your Ear Training

Practice with our interactive exercises designed by music educators

Neurobiological Foundations: Why Does Ear Training Work?

For years, music education was based on pedagogical intuition. Today, neuroscience confirms what teachers like Tomatis, Willems, and Kodály intuited: music is one of the most comprehensive activities for the human brain.

Activated Brain Areas

When we listen to music, the following are simultaneously activated:

- Auditory cortex: Processes and interprets sounds

- Motor cortex: Coordinates bodily and vocal responses

- Prefrontal cortex: Manages memory, attention, and analysis

- Hippocampus: Consolidates long-term memory

- Associative areas: Establish connections between hearing, vision, and movement

- Vestibular system: Integrates rhythm, balance, and spatial perception

- Emotional centers (amygdala, limbic system): Process affective meaning

Tomatis's Discovery: The Energy of Sound

A crucial discovery, demonstrated by French researcher Alfred Tomatis, is that the ear acts as a "dynamo" that transforms acoustic stimulation into neurological energy that feeds the brain.

Especially important is that high frequencies charge cortical energy, improving:

- Concentration and memory

- Motivation

- Brain vitality

- Sustained attention capacity

Conversely, sounds poor in high harmonics tend to exhaust the individual.

Proven Benefits

This explains why musicians and music students often show:

- Better memory in general (not just musical)

- Greater concentration and sustained attention capacity

- Better academic performance, especially in language and mathematics

- More balanced development between brain hemispheres

- Greater resilience to stress and depression

- Improvement in linguistic and reading skills

Neuroplasticity: The Brain Can Change

Ear training also promotes neuroplasticity: the brain's ability to reorganize and form new neural connections.

This is especially powerful in childhood but also occurs in adults and older people, revealing that it's never too late to develop your musical ear.

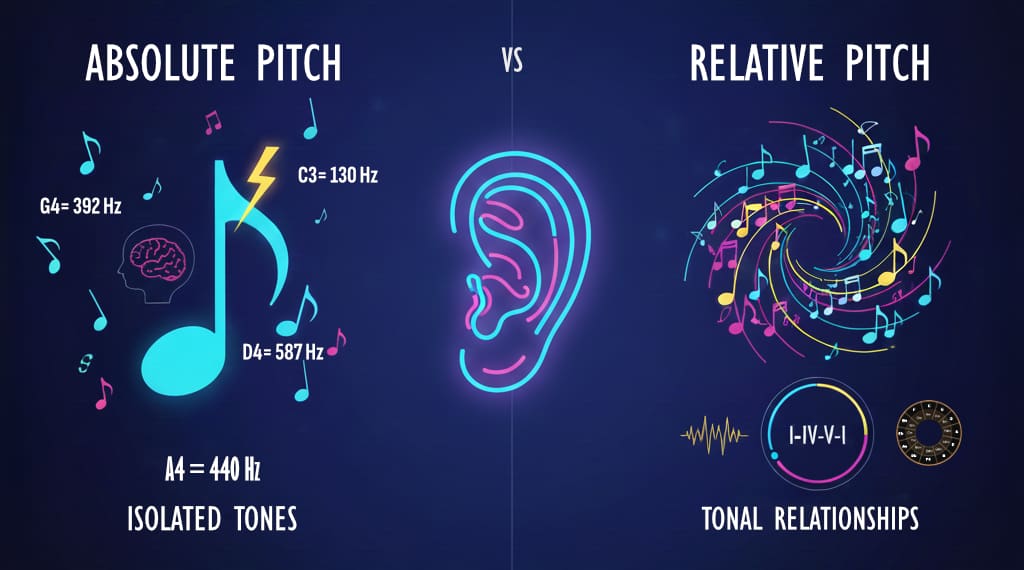

Perfect Pitch vs. Relative Pitch: Two Complementary Skills

Historically, ear training has been dominated by the distinction between "perfect pitch" (also known as absolute pitch) and "relative pitch." Understanding both is essential for designing effective ear training.

Perfect Pitch: Identifying Isolated Tones

Perfect pitch (absolute pitch) is the ability to identify or reproduce a specific musical note without an external reference.

A person with perfect pitch can hear a sound and immediately say "it's an A at 440 Hz" or, conversely, hear the instruction "sing a C" and produce that tone accurately, without needing a prior reference.

How common is it?

It's a rare ability. It's estimated that fewer than 1 in 10,000 people in the general population possess it, though it's more common among musicians (up to 1 in 100).

Advantages of Perfect Pitch

- Quick identification of isolated tones

- More fluent sight-reading

- More accurate musical dictation

- Facilitated memorization of complex melodies

- Performance from memory without sheet music

- Useful in atonal music (where there's no tonal context)

- Perception of unique characteristics of keys

Limitations of Perfect Pitch

- Interferes with transposition: A musician with perfect pitch hearing a transposed melody may be confused

- Difficulty with non-standard tunings: Early music at 415 Hz may be perceived as "out of tune"

- Some inflexibility: Emphasis on isolated tones can weaken perception of tonal relationships

- Not necessary to be musical: Many great musicians lack perfect pitch

Relative Pitch: Recognizing Tonal Relationships

Relative pitch is the ability to recognize musical intervals (distances between two tones) and tonal relationships.

Given a first reference tone, a musician with relative pitch can:

- Identify the second tone by naming the interval

- Reproduce it vocally

- Recognize harmonic progressions

- Understand keys and modulations

Relative pitch is much more common than perfect pitch and is the fundamental skill for Western music, which is based on tonal relationships (melody, harmony, tonality) rather than isolated tones.

Advantages of Relative Pitch

- Transposition without difficulty: The relative pattern remains invariable

- Understanding of scales and keys: You understand harmonic function

- Perception of harmony: Recognize chords and progressions

- Recognition of musical form and structure: See the architecture of the piece

- More natural improvisation and composition: Create without sheet music

- Fundamental for playing with others: Perceive relationships between voices

- Develops naturally: With musical exposure

- Can be acquired at any age: It's never too late

Current Pedagogical Consensus

Modern music pedagogy proposes that relative pitch should be the educational priority, although without ruling out the development of perfect pitch when it emerges naturally.

As academic research states: "Although perfect pitch may be an advantage in specific tasks, relative pitch is indispensable and much more useful in the context of the Western musical system. Both skills can (and should) be worked on in parallel."

Systematic Practice: How to Train Your Ear at Home

For ear training to be effective, it requires regular practice (ideally daily or near-daily). Here's a research-based protocol.

Fundamental Principles

1. Consistency over intensity

15-30 minutes daily is more effective than 2 hours weekly. Neuroplasticity requires repeated stimulation.

2. Variety

Alternate between intervals, chords, melodies, rhythm. Alternate between passive listening, vocal imitation, transcription, analysis.

3. Meaningful musical context

Practice with songs, repertoire fragments, not just abstract exercises. Emotion facilitates memory.

4. Feedback

Verify your answers. If possible, work with a teacher who corrects; if not, use apps that provide feedback.

5. Clear progression

Start with broad discriminations (low vs. high, major vs. minor) and advance toward subtleties (complex sevenths, altered chords).

Session Structure (30 minutes)

Minutes 0-5: Sensory Warm-up

- Listen to a complete piece of music (2-3 minutes) that you enjoy

- Goal: pleasure, not analysis

- Free movement to sound (rhythmic clapping, melodic gesture with arms)

Minutes 5-10: Interval Recognition

- Listen to interval pairs (e.g., major third vs. minor third)

- Respond verbally or draw the melodic contour on paper

- Use app or interactive exercises: Interval training

Minutes 10-20: Melodic Dictation

- Listen to a short melody (4-8 measures)

- Sing the melody on "la" (without lyrics)

- Try to write in notation (or describe intervals if you don't yet master notation)

Minutes 20-28: Harmonic Analysis (if already intermediate level)

- Listen to harmonic fragments (chords or chorales)

- Identify chord types, tonal functions

- Practice with our chord exercise

Minutes 28-30: Inner Hearing

- Read a score (without sound) and imagine how it sounds

- Alternate with real listening to verify

Practical Resources

For Beginners:

- Use free apps or our interval module

- Sing popular songs you like, paying attention to intervals

- Listen to instrumental music (classical, jazz) focusing on melody

- Practice simple vocal imitation: teacher or app sings 2-3 notes, you repeat

For Intermediate Level:

- Melodic dictations from standard repertoire (classical music, popular songs)

- Chord recognition (access our chord exercise)

- Bass transcription in small fragments

- Analysis of basic harmonic functions

For Advanced:

- 4-voice dictations

- Identification of altered chords, modulations

- Transcription of jazz, pop, chamber music fragments

- Inner hearing (mental score reading)

Proven Methods: Pedagogical Approaches That Work

Three 20th-century pedagogues have left particularly influential legacies in ear training. Their methods, though different in details, share common principles supported by neuroscience.

Willems Method: The Ear, Heart, Mind, Hand

Pedagogue: Jacques Willems (Swiss, 1902-1960)

Central principle: Harmonious and integrated development through four pillars.

Characteristics:

- Sensory listening first: Music is learned by ear before theory

- Emotion and meaning: Emotional connection with music (meaningful songs, not decontextualized exercises)

- Body movement: The body internalizes rhythm; gesture facilitates melodic understanding

- Singing as a tool: The voice is the most accessible instrument for integrating melody and harmony

- Natural progression: From the sensory (rhythm) to the affective (melody) to the intellectual (harmonic analysis)

Kodály Method: Music for Everyone

Pedagogue: Zoltán Kodály (Hungarian, 1882-1967)

Central principle: Everyone can be musical. Music education should be for all, based on folklore.

Characteristics:

- Relative solmization (movable do): Each note is a tonal function, not an absolute

- Vocal music: The human voice is the starting point (economical, accessible, expressive)

- Folklore as curriculum: Folk songs are the main pedagogical material

- Four qualities to develop: Trained ear, trained mind, trained sensitivity, trained hands (on instrument)

- Hand signs: Manual symbols to represent relative pitches

Suzuki Method: Talent Education

Pedagogue: Shin'ichi Suzuki (Japanese, 1898-1998)

Central principle: "Musical ability is not innate but can be developed in any child."

Characteristics:

- Learning by ear first: As children learn their mother tongue (through listening and imitation)

- Music-saturated environment: Constant passive exposure (recordings of standard repertoire)

- Parental participation: Parents also learn; they are models and daily reinforcement

- Repetition and refinement: The same fragment is played hundreds of times, improving each iteration

- Early start: Ideally before age 4

- Chosen instrument: Traditionally violin, though expanded to others

Synthesis of the Three Methods

The three pedagogues converge in that ear training is:

- ✓ Experiential, before conceptual

- ✓ Emotional, before abstract

- ✓ Vocal, before instrumental

- ✓ Folk/accessible, before academic

Theory comes later, as a tool to understand what you already feel and hear.

Myths and Realities about Ear Training

There are false beliefs that discourage many people from developing their musical ear. Here they are debunked based on evidence.

Myth 1: "You either have a musical ear or you don't."

Reality:

Auditory ability is partly innate (some have a predisposition), but it's mainly acquired through training. Studies show that anyone, at any age, can significantly improve their ear with systematic practice.

Pedagogue Suzuki emphasizes: "Musical ability develops, it's not born."

Myth 2: "Having perfect pitch is essential to be a musician."

Reality:

On the contrary, many great musicians lack perfect pitch and develop exceptional relative pitch. Perfect pitch can even be a disadvantage in certain contexts (transposition, non-standard tunings).

Current pedagogy emphasizes that relative pitch is more important and useful for most musicians.

Myth 3: "Ear training is boring and abstract."

Reality:

The best ear training programs are experiential, playful, and contextualized in music the student loves. Methods like Willems and Kodály demonstrate that ear training can be deeply pleasurable.

Modern gamified platforms confirm this: when practice is engaging, results improve and motivation is sustained.

Myth 4: "The ear cannot be trained after age 7-9."

Reality:

There's a critical period (3-9 years) where learning is faster and easier, especially for perfect pitch. But relative pitch can be effectively developed at any age, even in adults.

Myth 5: "I need musical literacy (notation) to train my ear."

Reality:

Notation is a tool, not a prerequisite. In fact, proven pedagogical practice is inverted: first you develop auditory ability (listening, imitation), then you learn to symbolize it (notation).

Many traditional musical cultures lack written notation and have highly developed listening skills.

Conclusion: Why Ear Training Transforms

Ear training is not a luxury for professional musicians. It's a fundamental tool for cognitive, emotional, and sensory development that benefits anyone, musician or not.

When you train your ear, you don't just improve at recognizing intervals or chords. You transform your:

- Memory: Better retention of information in general

- Attention: Ability to concentrate on details

- Language: Better phonetic discrimination, ease in learning languages

- Mathematics: Rhythm and harmony are mathematical structures

- Emotion: Greater sensitivity to emotional nuances, better expression

- Creativity: Internalized sound imagination allows mental creation

That's why pedagogues like Kodály insisted: "Music is for everyone. A society that doesn't cultivate ear training is a society that impoverishes itself."

Start Your Training Today

At Musicalia.io, our mission is to democratize access to quality ear training, using digital tools but never losing the experiential, playful, and emotional essence that makes learning deep and lasting.

Every interval you recognize, every melody you sing, every chord you identify—you're transforming your brain, enriching your sensitivity, connecting with an ancient human tradition.

Access now:

- Start with Interval Training — Master the identification of melodic distances

- Continue with Chord Exercise — Recognize harmonic qualities and progressions

- Practice regularly — 15-30 minutes daily, adapted to your level

Your ear will thank you. 🎵

Interactive Ear Training Exercises

Develop your musical ear with adaptive progression and immediate feedback